Most of my work over the past few weeks has revolved around editing. I just finished making final edits to the first pass of my book, I’m self-editing a forthcoming op-ed, and I’m in the middle of editing literally hundreds of writing assignments from my students. (Wish me luck!)

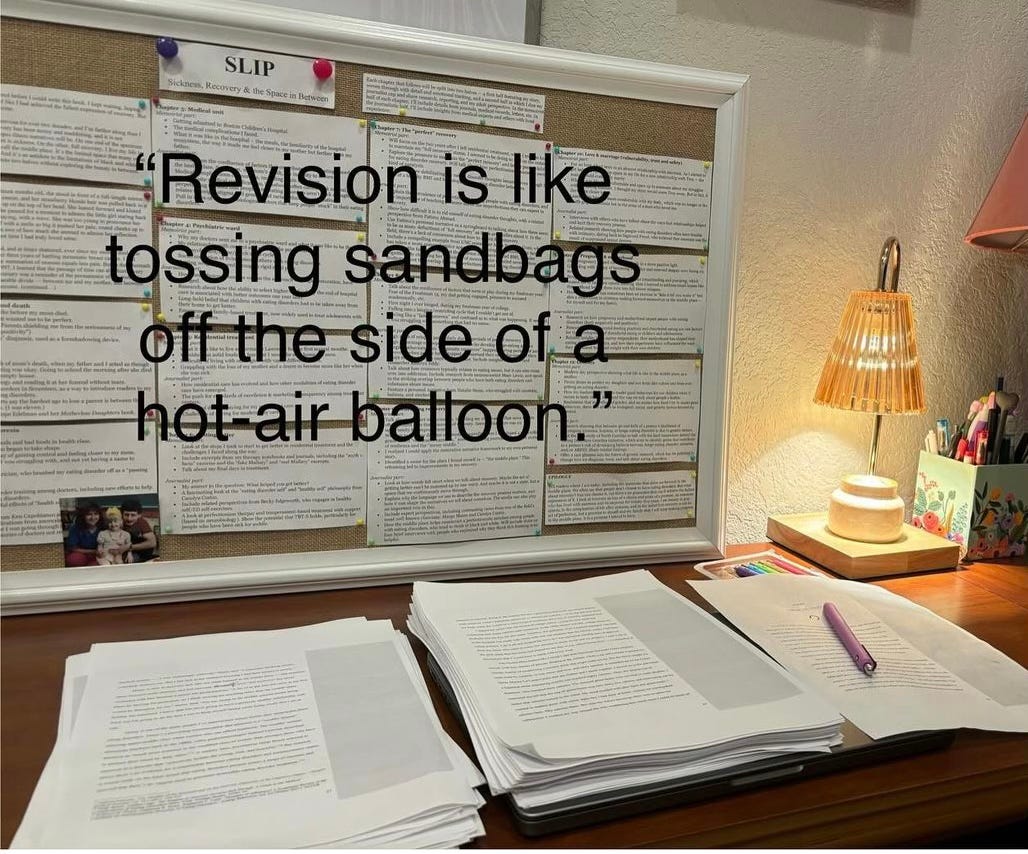

Sometimes editing feels frenzied. Other times, freeing. As Leslie Jamison writes in her latest book Splinters: “Revision is like tossing sandbags off the side of a hot-air balloon.” It’s not tinkering, she says. It’s flight.

When I posted this quote on Facebook recently, some of my writing colleagues phrased the editing process differently. One said writing is about “firing every word that doesn’t do a job.” Another said: “To me (when revising my own work), it has often felt like being tossed out of the airplane … without a parachute.” And another equated it to going to the nail salon: “To me it’s like getting a manicure and a pedicure. Cut off stuff you don’t need. Then polish what is left. If it doesn’t look good, use polish remover.”

Whatever metaphor you use to describe editing, at its most basic level it’s about growth. Editing helps you grow as a writer, and writing helps you grow as an editor.

When I edit others’ work, I want to help them be better, and I want the process to feel fulfilling. The best editors I’ve had over the years gave me this sense of fulfillment. They helped shape the writer I’ve become, and I still refer to the lessons they taught me.

Drawing from their inspiration and my own lessons learned in former roles as a copy editor and managing editor, I’ve compiled 10 editing tips that I hope you’ll find helpful.

Be respectful. This seems like a no-brainer, but it’s worth mentioning. I always remind myself that we all come to the written word with different experiences, backgrounds, and levels of understanding. And truthfully, this what makes writing and editing so fun. When I give the same assignment to the 85 students in my large intro-to-journalism course, I love seeing how they all approach it slightly differently. Stories are never exactly the same, and neither are writers.

Remember the curse of knowledge. Always try to edit with readers in mind. Imagine them as smart, curious people who need a guide along the path to understanding. To reach these readers, you need to avoid the “curse of knowledge.” The term hearkens back to a 1990 Stanford University study in which graduate student Elizabeth Newton designated two groups of people: “listeners” and “tappers.” The tappers had to select a well-known song and tap out the rhythm on a table. The listeners had to guess the song. The tappers predicted the listeners would be able to identify at least 50% of the songs. But in reality, the tappers guessed only 2.5% of them. It’s a fascinating and humbling reminder that, just because we know something as editors doesn’t mean our readers do. When in doubt, edit with the mindset that readers know less about the topic than you do. “The key is to assume that your readers are as intelligent and sophisticated as you are, but that they happen not to know something you know,” Harvard University scholar Steven Pinker writes in his book Sense of Style. “The form in which thoughts occur to a writer is rarely the same as the form in which they can be absorbed by the reader.”

Do front-end editing whenever possible. The best editors don’t just swoop in at the end of an assignment; they work with writers from the beginning of the writing process by helping them think through their initial ideas and navigate challenges along the way. Of course, this isn’t always possible, but it’s ideal. I always tried doing this when I was a professional editor. Even when the writers on my team were working on a breaking news story, I’d still do a quick check-in with them before they started their reporting and then again before they began writing. Now, I try to do something similar for my students who are working on longer stories. For my Longform Feature Writing class, for instance, students have to report and write a 3,000- to 3,500-word story by the end of the semester. I have students first submit a pitch, then an outline, then a 500-word scene assignment, then a rough draft, then a final draft (each of which counts as an assignment). I also build in a 1:1 coaching session with each student. These various checkpoints allow for front-end editing along the way. Front-end editing is a time investment, but it often saves you time on the back-end because the piece you’re editing will be that much better as a result.

Do a sit-on-your-hands read first. It’s temping to want to start editing from the moment you start reading. But when time is on your side, try reading the story first, from beginning to end, and then start editing it. This will give you a greater sense of the story as a whole and the direction it’s headed in. If you know what’s coming, you can have more context and make more informed edits.

Line edit first, then copy edit. This tip may be less applicable if you’re solely responsible for line editing and have colleagues who copy edit. But in general, it’s best to separate these two types of editing so that you’re not trying to look for everything all at once. Line editing is when you edit with these elements in mind: structure, pacing, tone, transitions, and sentences/paragraphs/sections that aren’t quite working. Copy editing is when you look for finer details: typos, grammatical errors, stylistic errors, word choice, name misspellings, etc. I like to think of it this way: When I line edit, I’m putting on my reading glasses. When I copy edit, I’m using my magnifying glass. If you try to do both types of editing at once, you’ll likely miss something.

When giving feedback, start off with the parts that worked well. Some writers get intimidated by the editing process, especially when working with a new editor for the first time. Be mindful of this when giving feedback. I always like to start off with what worked well by highlighting a few specific examples. Then I work my way toward what needs improvement. Taking a strengths-based approach to editing builds trust and respect, and it then makes critical feedback seem more well-intentioned.

Don’t be afraid to offer tough love. When editing (and when getting edited), I often think of a great quote from memoirist and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Anne Hull: “Reviewing a draft with my editor is a tough-love session,” she wrote in Telling True Stories. “I don’t want to be loved unconditionally; I want to understand what’s wrong with my draft so I can improve it.” It’s helpful to remember this during moments when you may worry about pushback to criticism. The best writers (and the best writers-in-the making) want you to be a little tough on them. And if they don’t, you need to help them eventually see the value in tough love.

If you think you’re being too critical, consider offering feedback from a place of curiosity. I always watch my tone when I’m giving feedback so that it doesn’t come across as overbearing or accusatory. If I find myself getting frustrated by a not-so-great piece of writing, I’ll don my reporter’s cap and start asking questions to arrive at a better understanding of the writer’s choices and the root of the problem. Some examples:

I’m wondering what made you decide to start the story this way. Can you tell me about your thought process?

I’d love to hear more about your thinking behind this story’s structure. How did you arrive at it?

What made you want to include these particular details?

Remember that the best editors aren’t fixers; they’re coaches. One of the primary goals of editing isn’t to “fix” people’s writing; it’s to empower them to improve their writing on their own. I’ve occasionally worked with fixers who edited my stories and filled them with sentences and phrases that didn’t sound like me because they were in my editor’s voice, not mine. The best editors have coached me by giving feedback and then letting me make the necessary edits on my own, in my own voice. Coaching invites conversations, and it can open up opportunities for writers to push back if they don’t agree with an edit. Sometimes the disagreement stems from misunderstandings about the writer’s or editor’s intent and can be easily resolved. Fixing seems faster in the moment, and it often is. But it takes more time in the long-run; if you don’t empower your writers to make edits on their own, they’re likely going to keep making the same mistakes over and over again — and you’ll have to keep making the same edits time and time again.

As a fun exercise, ask your writers or students to resurface a piece of earlier writing (from a year or so ago). Then have them read the piece and make edits to it, drawing upon what they’ve been learning about the written word over the past year. Sit down with them and go over the edits so that you can recognize and celebrate their growth alongside them. This may seem like an exercise that would only be helpful for early career writers, but I’ve found it to be worthwhile at any stage of one’s career. I sometimes do it myself, and I’m always amazed by what I find. We deserve to take more time to celebrate growth. Editing — and good editors — help us do that.

How about you? I’d love to hear your own tips for editing other writers’ work. Please share your thoughts (or any related questions you might have) by clicking on the “leave a comment” button below! Also, a few weeks ago I shared 10 tips for becoming a better self-editor. Here’s the post, in case you missed it.

My debut book, Slip: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery is now available for pre-order! Pre-orders help expand a book's reach, and my hope is that this book reaches and helps as many people as possible. You can pre-order it wherever you buy books:

What a great article!! Obviously I have never edited anything but nursing notes, but I wish I had read this before I did those!!