10 tips for writing about family members in memoir & personal essays

Plus: A special discount on SLIP pre-orders

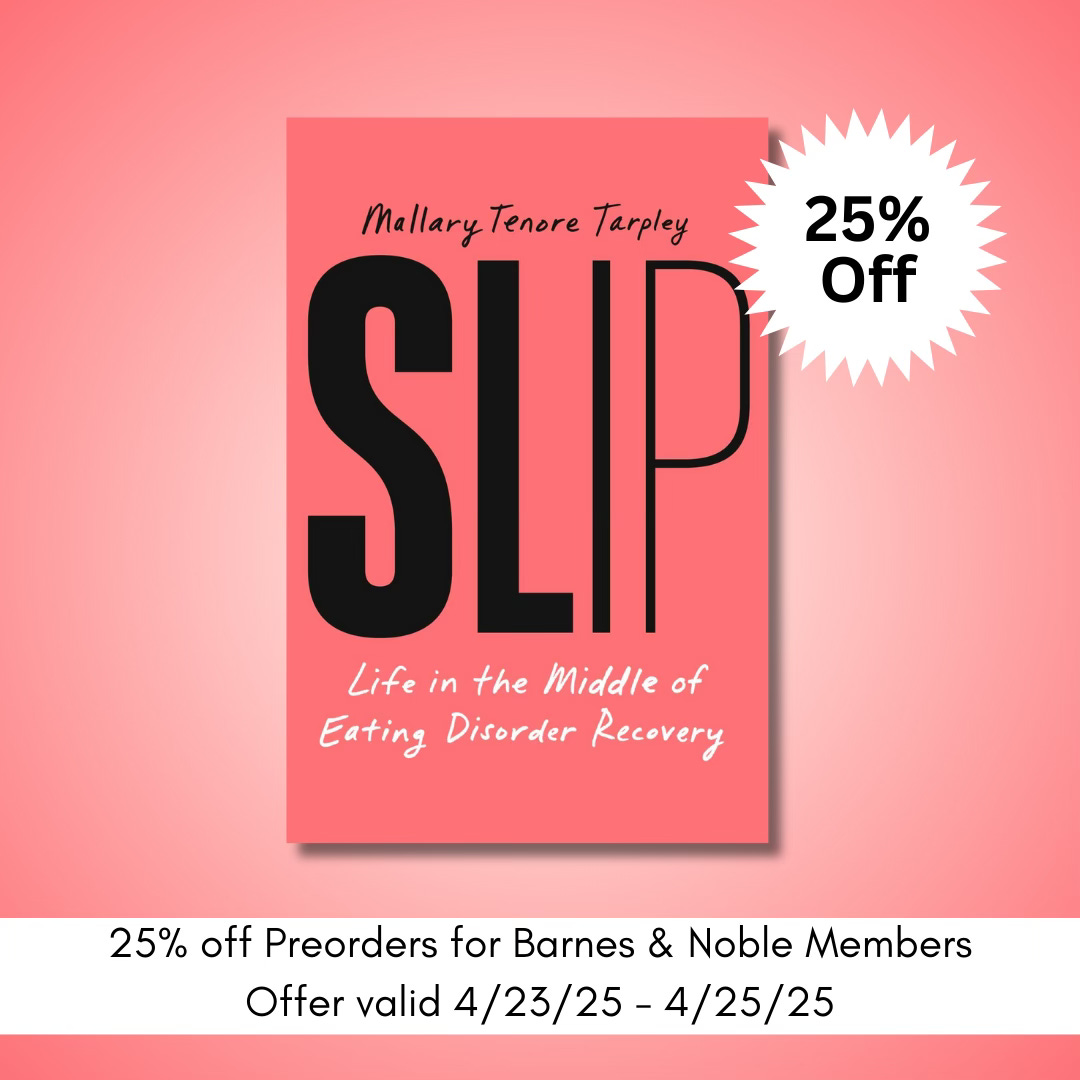

Write at the Edgers: This week, Barnes & Noble is offering a 25% off discount for pre-orders of my book SLIP. I’ve included more details at the end of this post. If you haven’t already pre-ordered, I hope you’ll take advantage of this offer!

To write a memoir is to accept the reality that you will need to have hard conversations not just with yourself but with your family. I knew this when I set out to write my own memoir, but I couldn’t begin to understand it fully until I began the reporting and writing process.

I learned that writing about family members is an art that requires a healthy mix of self-reflection, patience, acceptance, and vulnerability. Depending on your relationship with your family, the process may be painful or healing. In some cases, it may be both.

In the many years that I’ve spent writing about family members — and studying the topic in graduate school — I’ve gleaned some related lessons that I hope you’ll find helpful. Here are 10 tips to keep in mind:

1.) Determine your intent.

When writing about family, it’s always important to ask yourself: Why do I want to write about this family member, and in what ways will it advance the storyline? Are the details I’m including about this person pertinent to my story? And will I be the first person to reveal these details publicly? Asking these questions can help you reflect on your intentions.

This is especially important if you’re writing about a family member who has mistreated you in some way. In these instances, you want to make sure that you’re not writing solely from a place of blame, anger, or spite. It’s not to say that you can’t feel these emotions, but if writing is your only outlet for expressing them, then your prose may end up being more reflexive than reflective. I’m of the mindset that writing can be therapeutic, but it’s not therapy.

Personally, I journaled a lot about my family members before interviewing them and writing about them in my book. Doing so helped me parse which details belonged in the story and which ones were better left private.

2.) Be careful not to mythologize or demonize.

I used to wear rose-colored glasses whenever writing about my mother. She passed away from metastatic breast cancer when I was 11, and for a long time, I didn’t want to say or write anything bad about her. I praised her in every personal essay I wrote — to the point where one of my mentors finally asked me:

“Did your mother ever do anything wrong?”

“Yes, of course,” I told him.

“Well, you wouldn’t know it from your writing…”

He was right. I started journaling about all the times when my mother yelled at me or tried to make me feel insecure. From there, I decided what I felt comfortable sharing publicly. In writing about her flaws, I came to realize that her imperfections made her seem more relatable — to me and to readers.

When we characterize family members as all good or all bad, we render them one-dimensional. When we show their flaws, we can make them come alive on the page.

3.) Consider if it’s your story to tell.

I write a lot about my mom in my book because her death was one of the main factors that led to my childhood eating disorder. Once I ditched those rose-colored glasses, I wrote much more freely about my memories of her. But there was one part that I wrote with reservation — when talking about how she was sexually abused as a child. This part reads:

My mother didn’t live long enough to watch me go on my first date or to the prom with my high school crush. But she did offer a bit of counsel when I was ten.

“Don’t have sex until you’re married,” she told me one evening. “Then you can share that moment with someone who truly loves you.” Without going into detail, my mother told me she was sexually abused as a child, losing her virginity without her consent.

“Promise me you’ll wait?” she asked. It was more than a question.

“I promise, Mom,” I said, determined to keep my word. “I promise . . .”

It was the only time she mentioned the abuse to me, and the only time she spoke to me about sex. I was so rattled by the revelation that I held on to every word for years to come.

I went back and forth about whether to include my mother’s abuse because, in many ways, it didn’t feel like my story to tell. And since my mother is no longer alive, I couldn’t ask her about it. I ultimately decided to include this one passage about the abuse because it helped explain part of my own story — specifically why I felt so uncomfortable with intimacy throughout my young adulthood. Putting a tight frame around this part of her story, and being clear about how it related to my own narrative, made me feel more comfortable including it.

4.) Strive for specificity.

Many years ago, I wrote a personal essay about my mother and mentioned in a somewhat offhand way that she “wasn’t well educated.” I was referring to the fact that she had graduated from a vocational high school and had never attended college. But I didn’t explain this, let alone elaborate on it, in the essay.

When my maternal grandmother read the piece, she took great offense to the “wasn’t well-educated” part. She told me that my mother got good grades, worked hard to earn her high school diploma, and was incredibly smart. My grandmother was right, and in that moment I thought about how generalizations (“she wasn’t well-educated”) can lead to misconceptions (“she mustn’t have been smart”).

Sometimes, our own implicit biases get in the way, and we end up writing descriptions that lack context. In the absence of context, readers draw their own conclusions (sometimes accurate, often not) about a person. Writing that is specific helps paint a fuller and more accurate portrait.

5.) Experiment with the second person.

In his searing memoir Heavy, Kiese Laymon addresses his mother in the second person. I found this to be such a creative approach. I remember feeling as though I could hear Laymon speaking directly to his mother and could sense the emotions that he must have felt in the heated moments he was describing.

If you’re having trouble embracing the messy parts of your relationship with a family member, try writing to that relative in the second person and see what comes up for you. Notice, in particular, how the tone changes. This can clue you in to untapped emotions and/or details that might be worth exploring further. The second person isn’t necessarily the right fit for every piece, but it could be worth experimenting with in early drafts.

6.) Favor the ampersand.

Writing about family is messy, and there’s a temptation to want to clean up the mess before readers see it, or to pretend it was never there in the first place. But it’s in the mess that we find meaning.

To write about the messiness, we have to be willing to explore the dualities of a situation. I thought about this a lot after reading Tara Westover’s Educated, in which she explains what it was like being raised by survivalists in the mountains of Idaho. Westover’s editor, Hilary Redmon, said this about the book: “The people we find in her world are indelible, sometimes brutal, but also very human because Tara loves them and allows us to see them in all their complicated glory … She makes the alien familiar and the familiar surprising.”

This is one of the highest compliments a memoirist can get, and I think it stems from Westover’s ability to recognize the ampersands in her family life. In an interview about her book, Westover said: “My parents did their best. And their best was tragic. They did their best. And their best was devastating.”

As heartbreaking as this quote is, it’s also deeply evocative. I think the most important part is the word “and,” or put differently, the ampersand — a powerful form of punctuation that can hold together two seemingly opposing truths. So much of life exists in the space between such truths, where we come to develop a more nuanced understanding of family members and the ways in which they’ve shaped us.

7.) Describe your family’s shape.

It’s common to think about how family has shaped us, but far less common to give thought to the actual shape of our family. I reflected on this after reading Kathryn Schulz’s beautiful memoir Lost & Found, which focuses on losing her father and finding her partner. In one passage, she writes:

One consequence of losing a parent — obvious enough, although it hadn't occurred to me beforehand — is that it reconfigures the rest of your family. All my life, it had been the four of us; to the extent that had ever changed, it had only been joyfully, in the direction of more. But part of mourning my father involved acclimating to a new family geometry, a triangle instead of a square. As a unit, we were smaller, differently balanced, and, at first, unavoidably sadder.

This stuck with me, and it prompted me to think about how my own family’s shape changed after my mother died. Inspired by Schulz, I wrote a related passage in a chapter about leaving home to go into residential treatment for anorexia as a teenager:

Dad told me he’d always love me, no matter how far away we were, and no matter for how long. He would be allowed to visit me, but I worried that all the time apart would further strain our relationship. I had always been the sturdiest line in our family triangle, the base that kept my mother and father connected in times of distress. But our triangle had collapsed, and now it was just me and Dad—two lost lines moving farther and farther apart.

The next time you write about family, challenge yourself to describe its shape.

8.) Acknowledge the malleability of memory.

Just as families have shapes, memory does too. Some memories expand over time. Others shrink, or disappear entirely. I thought about this a lot when interviewing my father, who helped corroborate my childhood memories. At times, we looked at photos or medical records together, or revisited places from our past, to help fill in the gaps that inevitably accompany the passage of time.

Some of the most frustrating moments arose when our memories didn’t align. In those instances, I interviewed other family members and friends, and I made note of the places where our memories differed and dovetailed. When writing about these misaligned memories, I turned to Mary Karr’s memoir, The Liars’ Club, for inspiration.

In it, Karr writes about how she and her sister would often have different memories of the same experience. Rather than just sharing her own recollections, Karr made note of the places where her memory and her sister’s differed. She did so in a way that was artful rather than confusing, and it made me trust her even more as a writer. (Karr’s book The Art of Memoir is also a fantastic read.)

9.) Use dialogue to help readers “hear” both sides.

In one part of my book, I wrote about how I didn’t cry after my mother’s death. I thought I was supposed to be “strong,” and tears felt like weakness. I wondered why my father hadn’t seem concerned at the time, and for many years, I was afraid to ask him.

But in eventual interviews, I came to better understand his perspective. I didn’t want to write about him in an unfair or biased way, so I considered what I could do to elevate his voice on the page. Rather than simply write about my interviews with him, I decided to use dialogue as a way of helping readers “hear” his side of his story. I introduced the dialogue this way:

Why did my dad send me to school the day after my mom died, and then let me come home to an empty house? Why didn’t anyone tell me it was okay to be sad? Had no one thought to question my perpetually cheerful demeanor? I sat with the weight of these questions for a long time, fearful of asking my father for answers. The daughter in me wanted to protect him from all the poking and prodding. But the memoirist in me wanted answers, even if they yielded painful truths. One day, nearly twenty-five years after my mom’s passing, I decided to probe.

“Did you ever see me cry in the days and weeks after Mom died?” I asked my dad, unsure of how he would react.

“Not in front of me . . .” he said, trailing off.

Silence sat between us.

The dialogue continued, and I followed it up with a bit of reflection that bridged my father’s perspective and mine. This approach made for a much stronger passage. The next time you’re having trouble writing about family members, try turning to dialogue and see if that eases the process. (Also, be sure to record your interviews; you’ll end up with a lot more accurate dialogue to pull from.)

10.) Consider if you want to share your writing with family ahead of time.

I know some authors who never shared their memoir draft with family members prior to publication, and others who couldn’t have imagined not sharing it with them. It’s such a personal decision, and there’s no right or wrong answer. The book Family Trouble by Joy Castro does a great job exploring this topic and includes related anecdotes from several authors.

I did end up sharing the book with my father. The journalist in me wanted to make sure I had gotten my facts right. But more so, the daughter in me wanted to make sure that my father felt comfortable with what I’d written about him. We are close at this point in our lives, and I didn’t want the book to drive us apart in any way. I talked with him about it by phone ahead of time and gave him a preview of all the parts that included him. I also gave him a heads up about passages that I thought he might find surprising or disturbing. To my relief, my dad told me he loved the book and didn’t request any changes. This gave me peace of mind at the time and continues to do so as the book nears publication.

When it comes to sharing, do what feels most comfortable for you — and what you think will be best for your relationship (whether it be strong or strained) with your family.

********

A special note: Today through Friday, Barnes & Noble is offering a special promotion on pre-orders for my forthcoming book, SLIP! I hope you’ll take advantage of it; as I shared yesterday on Instagram, pre-orders are hugely helpful for authors. The promo is available to anyone who is a B&N Rewards or Premium member. (If you’re not already a Rewards member, you can sign up for free.)

Here’s how to take advantage of the pre-order discount:

➡️ Go to barnesandnoble.com and search for SLIP by Mallary (or click here).

➡️ Add to cart and type in the promo code PREORDER25.

➡️ Purchase the book and know that you have my utmost appreciation! ☺️

To those of you who have already pre-ordered, thank you so much!

Mallary, what a generous and incredibly useful post. Thank you for sharing specific examples — what a gift to others who are working through memoirs or other similar writings.

So helpful.

BTW, "Lost & Found" is one of my favorite books!