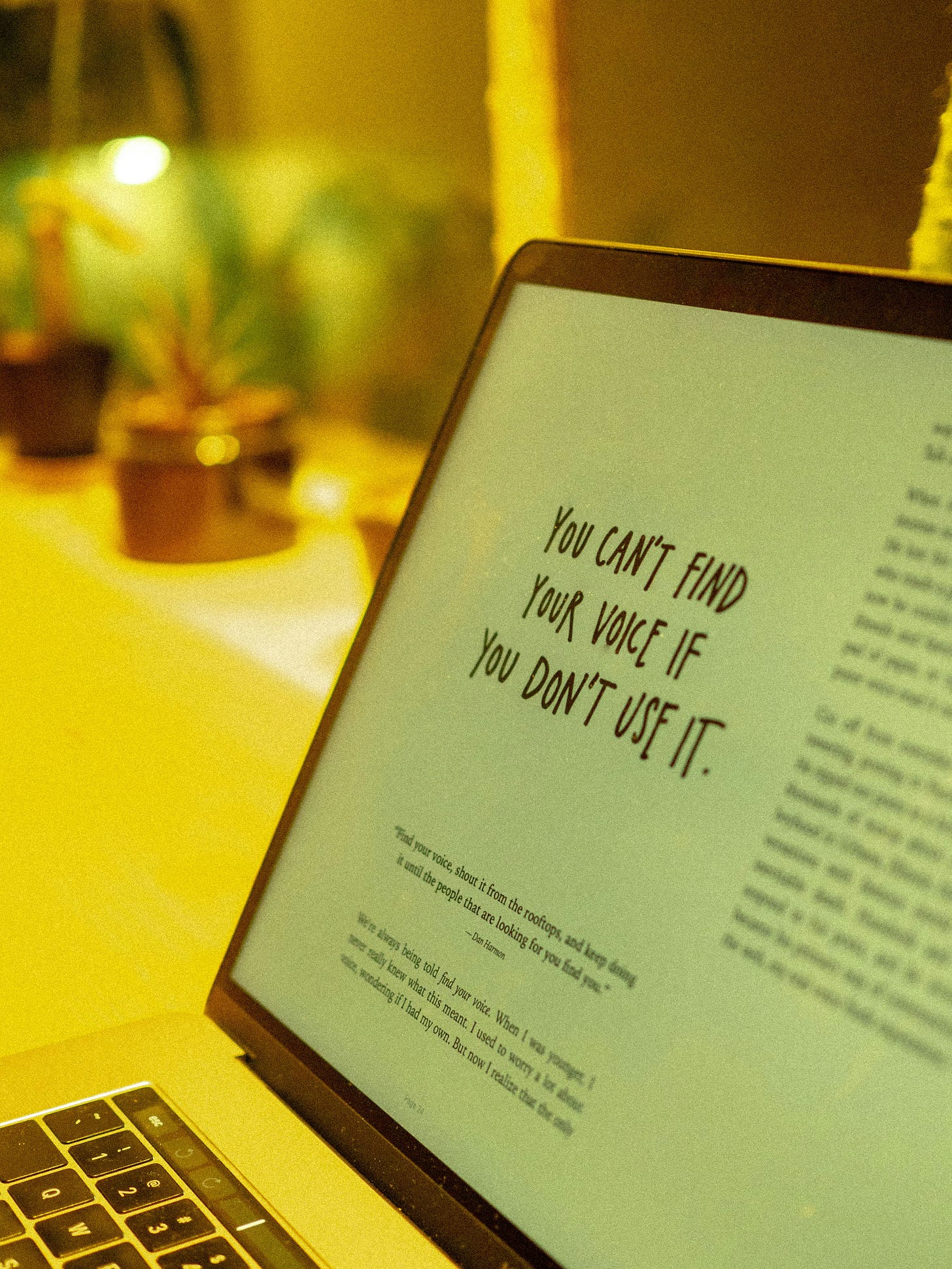

6 ways to develop your writing voice

We all have a voice; we just need to figure out how to amplify it.

A lot of my students ask me how to “find” their writing voice. I always respond by letting them know that they don’t need to search far. They already have a voice. We all do. The trick is figuring out how to develop and amplify that voice so we can more easily hear it — and so that readers can ultimately feel more drawn to it.

Voice is a slippery term that can be hard to define and refine, so I talk about it a lot with students in hopes of making it seem more accessible. There is not a one-size-fits all definition of “voice,” but I like this simple one from the late writing coach Don Fry: “Voice is the sum of all the strategies used by the author to create the illusion that the writer is speaking directly to the reader from the page.” At its heart, voice is about creating the illusion of conversation between writers and readers.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at some of the strategies that contribute to voice, along with specific examples.

Using different pronouns

Many of us were taught not to use the second person in our writing, but I like it when writers tactfully break this rule. Doing so can help you play with your writing voice, and it can create that illusion of conversation. Take this passage from Bob Kolker’s New York Times Magazine piece, “The Vanishing Family,” about living with the 50-50 chance of inheriting a cruel genetic mutation:

Even now, many in the family struggle with how to explain the impossible situation they’ve found themselves in. An earthquake or hurricane or war comes close — only a strange science-fiction version, something not visible or experienced by anyone but them; a disaster existing only inside their family’s genetic code. There were the facts — it’s inherited, anyone might have it — and there were the deeper questions raised by those facts. How do you feel safe, knowing that it is in your family’s essential nature to be fragile, ephemeral, ever close to expiration? How do you keep living when you know that everything that makes you a conscious person could disappear? If you were going to lose yourself — in a year, or two, or 10 — would you even want to know?

Kolker poses questions that the family is likely grappling with. But notice that instead of saying “they,” he uses the universal “you,” which helps us envision what it would be like to inhabit this family’s reality. It’s as though he’s talking directly to us.

Embracing subject matter expertise

I love reading stories written by journalists who have reported on a topic so rigorously that they know it inside and out. These journalists write definitively, with a voice of authority that inspires confidence and instills trust. Take this excerpt from a 2021 Wired piece that science reporter Maryn McKenna wrote about the pandemic:

This won’t be over soon. Between the slow pace of global vaccination and the rapid emergence of virus variants — potentially driven by the selective pressure that patchy vaccine coverage is putting on the virus — researchers and policymakers are beginning to admit that Covid-19 is here for good.

This requires a psychological reset. In the first year of the pandemic, we acted as though Covid was an unexpected guest, something that arrived without warning and could be packed up and sent away if we worked hard enough. It would be more realistic now to admit that the virus is an unwelcome permanent roommate. We are unlikely to force it to leave. But we may be able to keep it from taking over the house.

I love how McKenna gives us definitive statements — “this won’t be over soon” and “this requires a psychological reset.” And her use of the unexpected house guest metaphor makes her writing voice stand out even more.

Playing with punctuation

You may be thinking, what does punctuation have to do with voice? There’s actually a lot of overlap between the two. Some of my favorite writers use punctuation in creative ways that help me hear their writing voice. Take this example from Wesley Morris’ personal essay, “My Mustache, My Self,” published in The New York Times:

Like a lot of men, in pursuit of novelty and amusement during these months of isolation, I grew a mustache. The reviews were predictably mixed and predictably predictable. “Porny”? Yes. “Creepy”? Obviously. “ ’70s”? True (the 18- and 1970s). On some video calls, I heard “rugged” and “extra gay.” Someone I love called me “zaddy.” Children were harsh. My 11-year-old nephew told his Minecraft friends that his uncle has this … mustache; the midgame disgust was audible through his headset. In August, I spent two weeks with my niece, who’s 7. She would rise each morning dismayed anew to be spending another day looking at the hair on my face. Once, she climbed on my back and began combing the mustache with her fingers, whispering in the warmest tones of endearment, “Uncle Wesley, when are you going to shave this thing off?”

Morris uses the expected forms of punctuation (periods, commas, etc.), but notice how he also uses question marks, quotation marks, parentheses, and ellipsis. He puts seven words in quotation marks — porny, creepy, ’70s, rugged, extra gay, zaddy. It’s as though we can hear him saying these words out loud. The parentheses “(the 18- and 1970s)” act as a little aside and provide some comic relief.

Then there’s that great ellipsis, which creates a dramatic pause, as though Morris is taking a deep breath. He follows it up with one word that's at the heart of this essay: mustache. The passage ends with a question that seems to be on the minds of many in Morris’ family: “When are you going to shave this thing off?” The question propels us to want to keep reading — and to continue listening to Morris’ voice.

Inhabiting sources’ or characters’ voices.

In the early 1990s, Susan Orlean wrote a great story for Esquire titled “The American Man at Age Ten.” While working on the story, she spent a lot of time interviewing 10-year-old boys and trying to get into their headspace. If you read the story, you’ll see that Orlean doesn’t use highfalutin words or phrases. She instead gives a nod to her sources by writing in the voice of a young person. Consider this passage:

“Danny's Pizzeria is a dark little shop next door to the Montclair Cooperative School. It is not much to look at. Outside, the brick facing is painted muddy brown. Inside, there are some saggy counters, a splintered bench, and enough room for either six teenagers or about a dozen ten-year-olds who happen to be getting along well. The light is low. The air is oily. At Danny’s, you will find pizza, candy, Nintendo, and very few girls. To a ten-year-old boy, it is the most beautiful place in the world.”

Reading this almost makes you feel as though you’re listening to a 10-year-old describe the pizzeria. In a craft-related essay about the piece, Orlean wrote: “Sometimes, immersed in my reporting, I find myself thinking in the same rhythm as someone I’m writing about. This is part of my temperament; I tend to become caught up in other worlds. As long as I don’t slide into mimicry, it can help a piece of writing. You don’t want to hijack someone’s voice but draw inspiration from it. It is often a sign that you have submerged yourself deeply in a story, inhabiting it.”

Varying sentence length

One of my friends who started out in journalism and has since changed careers was great at writing short sentences. I used to be able to identify her stories without ever looking at her byline, partly because of how she varied her sentence lengths. (When someone can read your work and know it’s yours, that’s a sign that you have a distinct voice!)

I have a similar experience whenever I read Eli Saslow’s work. I’ve been drawn to many of Saslow’s stories, including this excellent Washington Post piece published in 2013. The story looks at how the parents of children who were killed in the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting were entering “into the lonely quiet” of loss. It’s a heartbreaking piece, and Saslow did a masterful job telling it.

Take this passage, which is about the parents’ visit to the Capitol, where they were recognized during a moment of silence on the House floor. Notice how Saslow varies the sentence lengths:

(Ana) Marquez-Greene listened to the names and pictured her daughter dressed for school that last day: pudgy cheeks, curly hair and a T-shirt decorated with a sequined purple peace sign — a peace Marquez-Greene was still promising to deliver to her daughter every night when she prayed to her memory and whispered, “Love wins.”

The gavel banged. The moment of silence ended. The parents sat back in their chairs.

The first paragraph is one long sentence that almost makes you feel as though you are sitting alongside Marquez-Greene as she thinks about her daughter. Then, you’re snapped back into reality as the gavel bangs. The three staccato sentences in that last paragraph are separated by three periods that act as stop signs (or, more fittingly, “full stops” as they say in the U.K.) The periods slow down the pace of information and give us a chance to take a breath in the midst of a heavy story. The mix of short and long sentences adds variety to the writing and contributes to the overall voice of the piece.

Using original language

My favorite writers avoid cliches and use original language that I haven’t heard elsewhere. This original language amplifies their voice, helping them to stand out as a soloist in an otherwise crowded choir.

I thought of this when reading Victoria Chang’s book of poetry titled Obit. In it, she writes about how she found herself wanting to stop time after her mother died. There are a lot of cliches related to time (turn back the hands of time, in the nick of time, once in a blue moon, etc.), but Chang opted for originality. She wrote that she wished she could “pull the arms off the clock.” This image (which has always stuck with me) plays upon sight and touch, as well as the sound of Chang’s writing voice.

I sometimes do a related exercise with my students in which I give them a list of cliches — (he was a broken record; the calm before the storm; goes against the grain; like finding a needle in a haystack; white as snow; quick as a bunny; every cloud has a silver lining; the grass is always greener on the other side, etc.) — and then ask them to rewrite the cliches in their own original way.

I then have them read their writing out loud. Doing so, I tell them, helps you catch mistakes, wordiness, and redundancies. It also gives you an opportunity to hear what you sound like as a writer. As you listen to yourself, consider what adjectives you would use to describe your voice. By hearing and describing your writing voice, you can more easily fine-tune — and “find” — it.

I’d love to hear from you! Which tips resonated with you? And what additional tips do you have for developing your writing voice?

P.S. If you’re here in Austin, I hope you’ll join me and other local writers for next week’s One Page Salon, an event hosted by the Writers’ League of Texas. I’ll likely read one page from my forthcoming book, Slip: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery. The event will take place at Radio Coffee and Beer on Tuesday, Feb. 4, from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m. More details here, and Facebook RSVP here.

Good post, Mallary. I think literary agents confuse the heck out of us writers when they say it’s the voice that captures their interest in a MS. We see that and we all scurry looking for the thing agents want in our own works. Readers don’t think of voice, they want characters with depth, with something to say or do even after being beaten down, they want conflict. Mushy characters kill a reader’s interest. I’d say write, write, write, with these in your stories and the writer will look back and say, “Oh, yeah, my stuff has voice. I see it now.”

These are great examples! The punctuation tip reminds me of Elizabeth Strout and her exclamation marks. Also Joan Acocella, a great stylist whose critical essays in the New Yorker I have missed since her death. I can't find a specific example right now, but I remember many instances of feeling totally disarmed by her sudden use of "you" or turn to the command mode. She's the kind of writer brave enough to begin a review of a dance performance with a phrase like, "Imagine you are Marie Antoinette." I love that chutzpah.