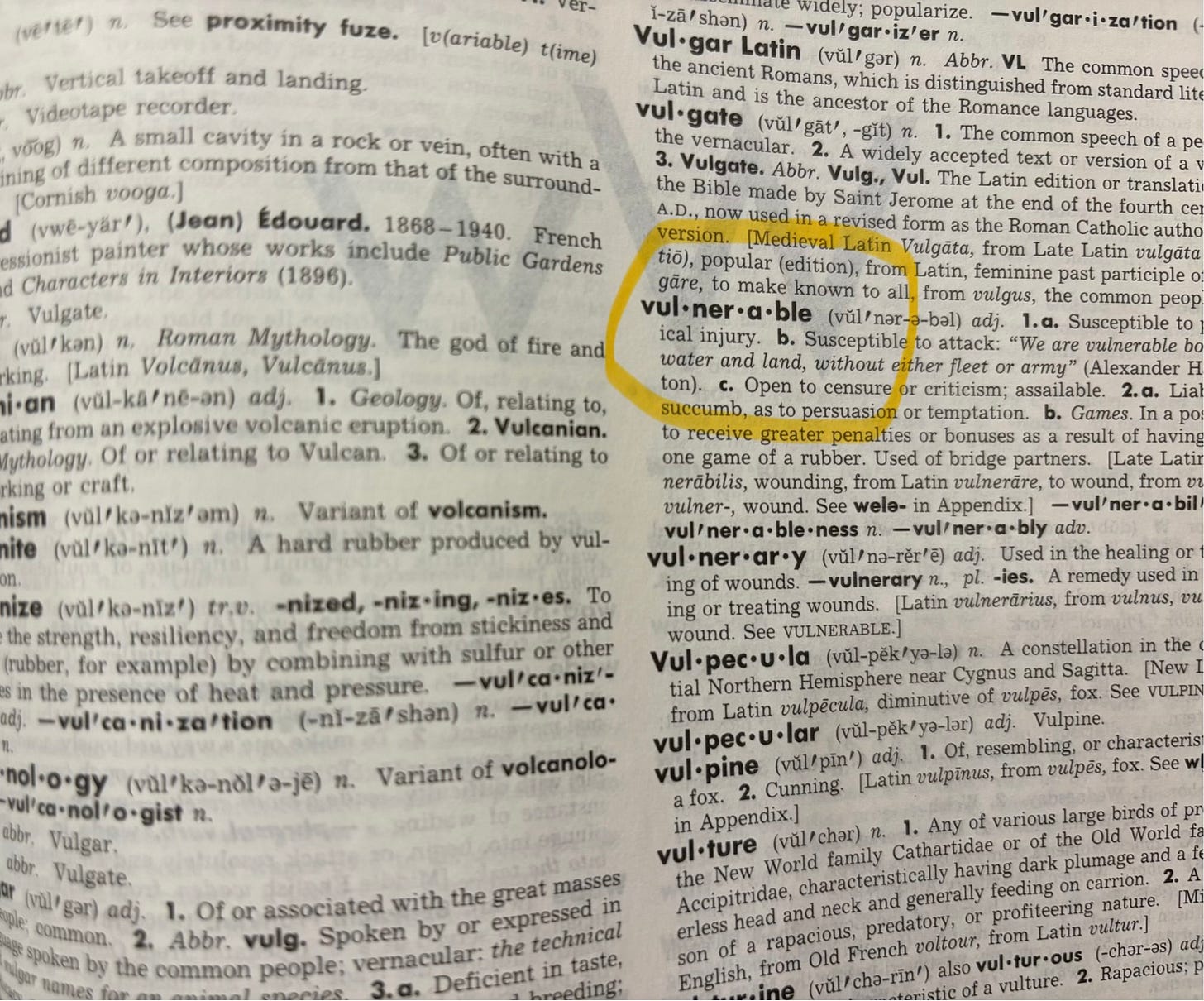

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the word vulnerability. It stems from the Latin word vulnus, meaning wound, and it’s a state of emotional exposure that many memoirists experience when putting their stories out into the world.

For a long time, I hid the hard truths of my eating disorder recovery story. After years in treatment as a teenager, the perfectionist in me wanted to achieve the fullest expression of recovery. I told everyone that I had an eating disorder, always framing it as a piece of my past without acknowledging that it was still a part of my present.

I was too afraid to admit that I wasn’t “all better,” too ashamed to confess that the care I received hadn’t “cured” me. I found myself in a space that I couldn’t define — someplace in between my sickest self and the recovered girl I made myself out to be.

In my forthcoming book SLIP, I write about how I eventually came up with a name for this space: “the middle place.” I came to define it as the messy middle in between acute sickness and full recovery from an eating disorder, a space where slips happen but progress is always possible.

By framing SLIP around the middle place, I want to show what it takes to engage with the world even as I traverse the space between sickness and full recovery, between no longer and not yet. I don’t mean to suggest that full recovery is not possible; for many people, it is. Nor do I want to imply that people in the middle place aren’t trying hard enough or are somehow settling. Living in the middle place isn’t about giving up on full recovery; it’s about viewing recovery as an ongoing, vulnerable process rather than a final destination.

I interviewed and surveyed hundreds of people about the middle place and found that it’s more populous than I would have ever imagined; more than 85% of my 718 survey respondents said they have found themselves in this place.

And yet, even though the middle place is prevalent, it’s often left out of the way we talk about eating disorders. When I was in my teens and twenties, I read countless books on eating disorders, most of which were either written by clinicians and/or fully recovered individuals. I saw my false narrative reflected in these books, the one where I pretended to be “all better.” But I didn’t see my actual narrative, and that lack of a mirrored image made me feel painfully alone. I began to think that the messiness of eating-disorder recovery was an untold — or at best half-told — story.

I understand why so many books advocate for the gold standard of full recovery; they offer readers a sense of hope and possibility during times when they need it most. Full recovery stories matter. But we need space for other stories too. When the majority of eating disorder books are written by fully recovered authors, we miss the opportunity to elevate the voices of other writers whose lived experience runs contrary to the types of narratives our society favors: those with protagonists who battle their disorders and then victoriously defeat them.

In recent years, I’ve taken note of writers who defy these “societal norm narratives” as I’ve come to call them. One of my favorite examples is Roxane Gay, whose propulsive memoir Hunger looks at what it means to live in a fat body in a fat-phobic world. Gay once told PBS NewsHour:

People seem to want us to have these triumphant stories, and there’s not a lot of space for the in-between, where you’ve suffered and you’re healed but things are maybe also not OK. When I wrote my memoir, Hunger, which was a memoir of my body, I was extremely worried about how it would be received because it required a level of vulnerability. I found it extremely uncomfortable to write about a fat body, while living in it, without some sort of triumphant weight loss narrative. And I certainly didn’t think anyone but other fat people would gravitate toward the book. But as I was touring it, not only in this country, but all around the world, I found that everybody lives in a body that is complicated and that they struggle with at one time or another. I think a lot of people are looking for language to talk about that.

I sought comfort in this quote a few years ago when trying to find a publisher for my book. And I do so now, too, as my Aug. 5 publication date nears and the book gets closer to being out in the world.

Early reviews of SLIP have been validating, and they suggest that the book will help readers feel seen, heard, and understood. And yet, I know that no book escapes critical reviews. I suspect some people may read SLIP’s synopsis and assume that I’m advocating for quasi-recovery or pseudo-recovery — two terms that are prevalent in the eating disorder field. Most often, they’re used to describe people who are working on their recovery but still struggle with disordered thoughts and/or behaviors.

I’ve never really liked the terms “quasi” or “pseudo” to describe recovery; they suggest that anything short of full recovery is somehow fake or only worthy of partial credit. Quasi-recovery and pseudo-recovery seem like more apt terms for people who say they’re fully recovered but actually aren’t. This used to be the case for me. And it remains a reality for many people who shroud their slips in secrecy because they feel shame and stigma around admitting that they’re still struggling.

I want to give voice to people in these situations — those of us who are better but not all better, who are always aiming for “more recovery” even if we haven’t been able to reach the fullest expression of it. I hope that by amplifying these diverse voices, I can broaden our collective understanding of the many ways that recovery takes shape.

The more we can illuminate the middle place, rather than dismissing it or denying its existence, the more honest we can be with ourselves and others. Over time, this honesty can lead to progress in recovery, as it did for me. And it can help us become more reliable narrators of our own life stories.

“When we deny our stories, they define us,” the social scientist Brené Brown, once said. “When we own our stories, we get to write a brave new ending.” It’s then up to us as to when, and whether, we want to share those narratives with the world. “The only stories I share with the public,” Brown has said, “are stories that I have really processed, and stories where my healing is not contingent on your opinion of those stories.”

This quote makes me think of my younger self, who wouldn’t have been able to write about life in the middle place out of fear of what people would think or say. But now feels like the right time in my life to write about it and build community around it. Through the writing process, I’ve met so many people who have told me, “I experienced that too” or “I’ve been waiting for someone to write a book about the grey spaces of recovery.”

Author Suleika Jaouad, who writes beautifully about in-between spaces, puts it this way: “I deeply believe that when we dare to share our most unvarnished vulnerability, when we dare to truthfully answer the question ‘How are you?’ and we are able to open ourselves up both to the incredibly hard facts of life and also the beautiful ones, we learn again and again that we’re more alike than we are different.”

Writing memoir is no doubt an act of vulnerability, but it’s also a hard-won act of service. As a memoirist, I hope SLIP ends up serving readers well — and that they get as much out of reading it as I did out of writing it. That would be the ultimate gift.

I’d love to hear from you! Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section.

I love what you have to say about vulnerability and also what you say about writing a memoir as being “hard-earned service.” I never thought of it that way, but that tracks for me…

I just came across your book and added it to my master list—such a cool surprise to see you pop up in my Substack feed! I’d love to add you to the directory I’ve put together (it’s live but I’m always adding to it). Congrats on your upcoming book—it takes so much bravery to share a story like yours.