Fact-check your way toward greater accuracy in writing

Favorite fact-checks from my manuscript

I’ve always identified as a writer, but I also like to think of myself as a copy editor with an appreciation for fact-checking. I was a copy editor in my first job out of college, and it expanded my appreciation for good grammar, adherence to style, and accurate prose.

Now, as a journalism professor, I teach my students that accuracy builds trust. I encourage them to hold a magnifying glass up to every fact in their stories so they can catch mistakes. There are different ways to “magnify” facts during the self-editing process. For me, this usually means printing out my stories and circling all the names and numbers as a visual reminder to double, then triple, check them.

Of course, the longer the copy, the more likely mistakes will find their way in. With every paragraph, every page, the entryway for errors widens. I’ve thought about this a lot while editing my 100,000-word book, SLIP: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery, which will be published next summer. Drawing upon personal narrative and reportage, the book provides an inside look at disorder treatment and offers up a new and overdue framework for understanding the recovery process.

I recently got notes back from my copy editor and fact-checker, two separate people who read my manuscript. Their work overlapped in some ways, but it was also distinct. The copy editor read my manuscript for style, syntax, grammar, etc. The fact-checker read it in search of mistakes, misinterpretations, misspellings, etc. Fortunately, the fact-checker’s notes were, as she put it, “super light.” But there were still instances in which I had misspelled names or used incorrect numbers when referring to data, even though I had done multiple rounds of my own fact-checking. The reality is, we can’t always catch everything on our own. And when others catch what we didn’t, it’s humbling.

As I read through my fact-checker’s notes, I was especially grateful for the smaller-scale corrections she made — ones that many people wouldn’t even notice but are nevertheless important. Interestingly, a lot of them were related to details from my childhood. Sometimes the closer we are to something, or the longer we’ve known about it, the less likely we are to fact-check it. It feels so true to us that it doesn’t even occur to us it could be wrong.

Here is a short list of passages that contained some of these smaller-scale fact-checks, along with the (paraphrased) corrections from my fact-checker:

On loving books as a child: “I read countless books in that Japanese maple tree, propping my body up against the strongest limb and losing myself in other worlds. I devoured The Secret Garden, The Little Princess, Tuck Everlasting, Bridge to Terabithia, and A Wrinkle in Time, wishing I could make my favorite characters come to life.”

As my fact-checker pointed out, the book’s title is A Little Princess, not The Little Princess. This was my favorite book growing up, and I’ve been incorrectly calling it The Little Princess this whole time!

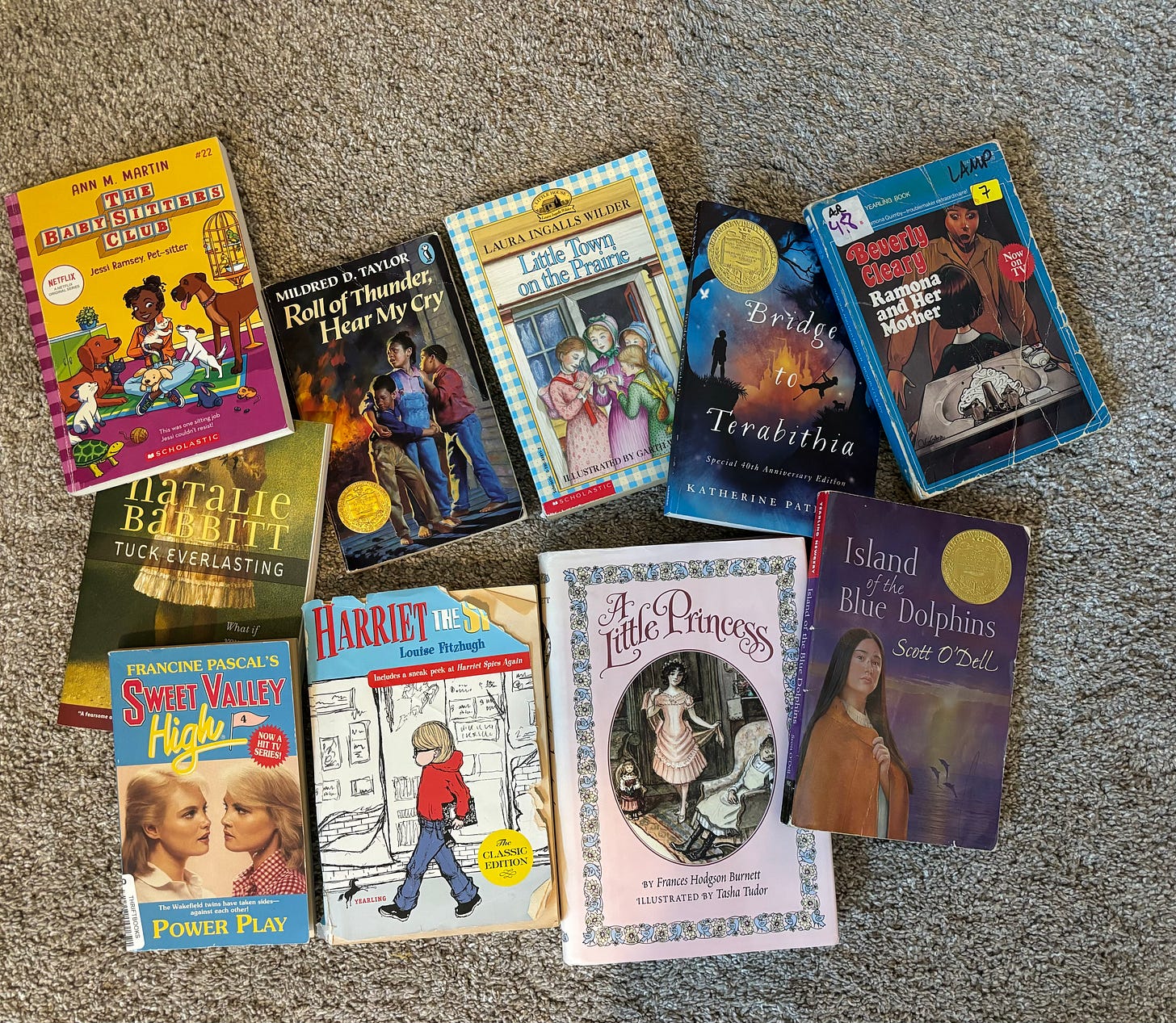

Some of the childhood books I revisited when writing my own book.

On hiding my tears the morning after my mom died, when I was 11: “I pretended to read a Babysitters Club book as I walked, hoping to find refuge in its pages.” And a later passage: “I hunted the attic of my childhood home, opening up boxes that revealed the bric-a-brac of childhood: my collections of Trolls, costume jewelry, and Babysitters Club books.”

It should be Baby-Sitters Club, not Babysitters Club. I had never paid attention to the hyphen, but now it’s the first thing I see.

On restricting my food intake as a 12 year old: “I started restricting more, eliminating all foods except ones that I deemed ‘safe’: cottage cheese, bananas, Lender’s bagel halves, and fat-free Snackwell’s cookies.”

It should be SnackWells, with a capital W. Just typing this word makes me cringe; these fat-free cookies were the epitome of the 1990s’ fat-free diet craze.

On obsessively exercising in the eighth grade while sick with anorexia: “In science class, when we learned about speed, velocity, and acceleration, I kept thinking about exercising. During a lesson about Isaac Newton, I fixated on his third Law of Motion: An object will not change its motion unless a force acts on it. I thought about anorexia’s force over me and my every motion.”

My fact-checker astutely pointed out that this is actually Newton’s first law, not his third. A good catch!

More on obsessively exercising (which, for me, played out in the form of jumping): “At 3:30 p.m., I would stand next to the green-quilted couch in the living room and jump to the entire opening song of Arthur: And I said hey! What a wonderful kind of day! When you can learn to laugh and play.”

I grew up watching the show Arthur and singing its theme song. I still know the lyrics by heart, but my fact-checker pointed out that I had remembered them incorrectly. The correct lyrics aren’t When you can learn to laugh and play, but rather If we could learn to work and play. (It makes sense that, as a kid, I would have swapped out “work” with “laugh.”) Here's a video of the theme song, which you’ll appreciate if you grew up alongside Arthur, the friendliest of aardvarks. It’s a short video that conjures up so many memories and emotions for me:

On seeing my EKG results during my first hospitalization for anorexia, at age 13: “Standing beside my bed, the nurse handed me a page with four rows of squiggles that my heart had drawn. They looked like the lines I used to draw on my red Etch-a-Sketch — grainy grey and never as straight as I would have liked.”

Turns out, it should be Etch A Sketch, with a capital A and no hyphens. It’s important to write brand names correctly!

On binge-eating as a young adult: “Alone in my apartment, I would sit at my kitchen table and write my stories with a half-gallon of Breyers Cookies and Crème ice cream.”

I accidentally made this binge food sound fancier than it actually is. (I’m sure there’s some interesting interpretation to be made there...) Per the actual flavor name, it should be “Cream,” not “Crème.”

On wanting to protect my children, Madelyn and Tucker, from harmful messaging about food and bodies: “Unknown to me, Tucker checked out a book titled The Berenstein Bears and Too Much Junk Food. The book was published in 1985, the year I was born. I loved the Berenstein Bears as a kid, so it’s quite possible I had once read it. …”

My fact-checker pointed out that it’s Berenstain Bears with an “a” instead of an “e.” The Berenstain Bears and Too Much Junk Food includes some misleading messages about food, and as I go on to explain in the book, I didn’t want my children reading it.

Many of these fact-checks had to do with missing punctuation or incorrect capitalizations and words. They are small fact-checks, but collectively, they make a big contribution to my book’s overall accuracy. This gives the writer (and copy editor) in me peace of mind.

How do you fact-check your own work (if at all)? What has worked for you, and what challenges do you still come up against? Leave thoughts and/or questions in the chat!

I loved reading this! I'm not at the fact-checking stage yet for my first book, but I really enjoyed learning about your process.

I agree about the trust piece. Most books I've read recently have had errors that really took me out of the moment. And these were bestselling authors with Big Five publishers. So I guess it is also reassuring that mistakes are probably inevitable and happen to everyone. But it's still worth doing our best to correct as many of them as we can!

A Little Princess was also my first favorite novel, and I, too, called it The Little Princess for years. I think it was because Sara Crewe was so singular to me! I remember that it felt like a revelation when I noticed the indefinite article, making my beloved Sara only one of potentially many little princesses in the world.