As a kid, I loved cuddling up with my grandmother and reading books beside her in bed. I would memorize the books she read to me and then “read” them back to her, determined to learn how to tell stories and one day write some of my own.

In junior high, I continued reading books out loud with my grandmother. Little Women, Jane Eyre, To Kill a Mockingbird, and A Wrinkle in Time were some of my favorites. Reading was my salve, especially after losing my mother to breast cancer when I was eleven years old. As an only child, I could escape into these books and inhabit new worlds that distracted me from my lived reality.

In the aftermath of my mother’s passing, I often felt as though I didn’t have words to describe the emotional toll of her death. Reading books made language feel more accessible, more expansive. I especially liked books that introduced me to words I didn’t know. I would draw circles around these words and use context clues to try figuring out what they meant, hoping they might help me to define and describe what otherwise felt like a wordless time.

“What does inscrutable mean?” I asked my grandmother while reading Mrs. Dalloway the summer after Mom died. “And what about mitigate? And ruffians?”

“Let’s look them up!” she said, as she always did whenever I asked her for a definition. She got out her old American Heritage dictionary — that tome of discovery — and ran her finger along the pages until she found inscrutable. “Difficult to understand or interpret; impenetrable.” It felt like a relatable word to me in the midst of such great loss. Gramz wrote it down on a sheet of lined paper, always keeping a running list of new words for her little logophile.

My seventh-grade markups in Mrs. Dalloway.

Moments like this helped shape the writer I’ve become, and I’m reminded of them often. Just this week, I thought of Gramz when getting an email with the subject line: “200 New Words and Definitions Added to the Dictionary!”

In a related announcement, Merriam-Webster previewed some of the new words: beach read, creepy-crawly, street corn, burrata, freestyle, true crime, spotted latternfly, and my favorite: badassery. Gramz passed away nearly a decade ago, but if she were still alive today, I could imagine her reading the definition (“the state or condition of being a badass”) with her eyes wide and her mouth agape.

As my grandmother’s granddaughter, I made note of the words and phrases I didn’t know from the list, including:

snog: “to kiss and caress someone passionately" (If I ever decide to write a romance novel, I’m going to have to use this.)

International Bitterness Unit: “a unit of measurement used to assess the concentration of a bitter compound found in hops in order to provide information about how bitter a beer is” (I’m not a beer drinker, so it doesn’t surprise me that I hadn’t heard of this.)

dungeon crawler: “a video game primarily focused on defeating enemies while exploring a usually randomly generated labyrinthine or dungeon-like environment” (As a mother of a son who doesn’t yet have video games but asks for them incessantly, I suspect I would have eventually come across this phrase.)

touch grass: “to participate in normal activities in the real world especially as opposed to online experiences and interactions” (Am I wildly out of touch for not knowing what touch grass meant?!)

As I read the new entries, I was reminded that language is ever-evolving and that writers should account for the current zeitgeist.

Earlier this week I shared the entries with some of my students, who often ask me how to expand their vocabulary. Reading, I tell them, is the best way. I encourage them to read, look up words they don’t know, and reinforce their understanding of these words by using them. I suggest that they sign up for Merriam-Webster’s “Word of the Day” email so they can learn new words daily. I also encourage them to look at examples of how a word is used in various sentences — and to listen to how it’s pronounced.

Sometimes, I tell my students a story about how I used to think I was so fancy as a kid because I knew and used the word cerulean (my favorite Crayola crayon color at the time). For months I pronounced it “ceru-lean,” until one day my grandmother corrected me. “It’s pronounced sə-ˈrü-lē-ən,” she said, drawing out each syllable in a way that forever stuck to my memory.

The more you use a new word in your writing, the more likely it will become part of your vocabulary. As the old adage goes, “Use it three times and it’s yours.” You just have to make sure you’re using (and pronouncing) it correctly — and that it’s the right fit for whatever you’re writing.

We’re sometimes taught that the bigger the word, the smarter we’ll sound. But the truth is, you shouldn’t use an SAT word for the sole purpose of sounding smart. Nor should you bog down copy with words that are so esoteric they distract from the message you’re trying to convey. This is especially true when writing about complicated subject matters. As my mentor Roy Peter Clark likes to say: At the points of greatest complexity, use the shortest paragraphs, the shortest sentences, the shortest words.

When the subject matter isn’t super complicated, it can be fun to put new words to good use. I used lesser-known words sparingly when writing my book, but every once in awhile I slipped them in. Here’s an example from a part of the book where I talk about how my father wanted to help me find my way as a teenager, both literally and figuratively:

“I wanted to arrive at places on my own, without my father telling me how to get there. But that changed when I moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, thirteen hundred miles from home. I longed for his guidance. In his absence, the hand-held GPS became a cicerone of sorts, channeling me along unfamiliar roads and toward new destinations.”

I learned the word cicerone (“a guide who conducts sightseers”) when reading Gabrielle Zevin’s bestselling novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. It spoke to me when I read it, and I knew I had to start using it.

In another part of my book, I mention “the recrudescence of a terminal disease” — a great word to describe the return of an undesirable condition. I learned this word when reading Arthur Frank’s thought-provoking book The Wounded Storyteller.

As a writer, I like to think that such words will appeal to the young Mallarys — readers who like to explore new words to expand their understanding of the world. And as a mother, I can see my younger self reflected in my children, who both love to read.

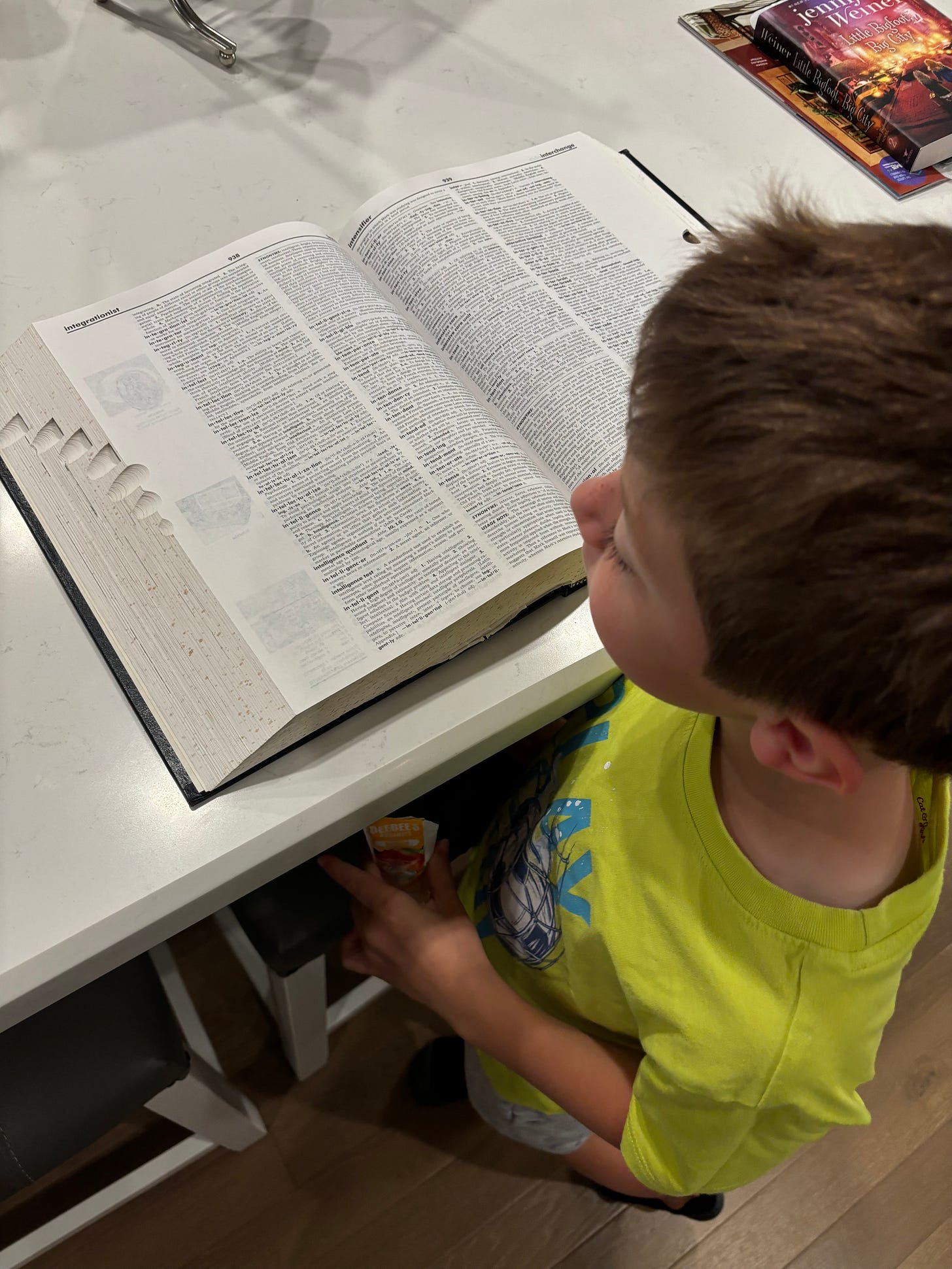

Tucker, reading our dictionary.

“Mommy, what does ‘integrity’ mean?” my seven-year-old son Tucker asked me this week.

“Where did you hear that word?”

“I don’t remember” he said, as he often does when I ask him to recount what he learned on any given school day. “I just heard it.”

“Well, let’s look it up!” I said, channeling my inner Gramz. I got out the American Heritage dictionary — the same one she and I used all those years ago — and ran my finger along the page until finding the word.

“Steadfast adherence to a strict moral or ethical code,” I told him.

“What does that mean?”

“It means being a good and honest person.”

“That’s a good word,” he declared.

I nodded my head in agreement and kissed him on the cheek. In that moment, with the dictionary on my lap and my son by my side, the only word I could think of was love.

Thanks, Mallary! Subscribed to word of the day.

Reading Gabrielle Zevin right now. Loving T, and T, and T!