How to get better at capturing details in interviews (Part 2)

I’m a big believer that if you teach writing, you should be actively engaged in the craft. For me this means book-writing, journaling, and writing freelance stories as time allows. Teaching informs my writing, and writing informs my teaching. I’ve found this to be especially true lately, during a stretch when I’m working on a few freelance stories at once.

Over the past week, I’ve been doing a lot of reporting for a magazine story I’m working on. While conducting interviews, I’ve applied some of the interviewing tips I wrote about last week and have been thinking about the ones that I’m about to share this week.

I hope these tips will give you a creative boost and will expand your capacity for capturing details during interviews. While most of them are geared toward journalists and authors, they can also be of service to researchers, oral historians, and storytellers in general.

1.) Be intentional about where you conduct your interviews.

I thought about this a lot when interviewing my father for my forthcoming memoir, SLIP. My dad and I live nearly 2,000 miles apart, so many of our interviews were done by phone. Whenever possible, though, I tried conducting them in person.

Some of our best interviews actually took place in the car. My dad’s a car guy, and he always seems at ease when behind the wheel. When we would talk side-by-side in the car, our eyes were usually fixed on the road, but our thoughts were turned inward. The “interviews” felt more like conversations and were a little less tense than if we had been sitting across from each other face-to-face discussing hard truths. I think we both got more out the conversations as a result.

Find the setting that work best for the person you’re interviewing, and be open to making adjustments as you go.

2.) Rely on the five senses.

My friend Jacqui Banaszynski has written about how interviewing is “a full-body sport,” and I think that’s true on many levels. To capture senses during interviews, you need to be attuned to what you’re seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching. Of course, you may not be able to take in all of these senses, but it’s good to be thinking about them. Simple questions like What did it sound like? and How did it taste? can go a long way toward capturing detail.

When writing personal essays and memoirs, you can also interview yourself with the five senses in mind. I did this a lot when writing SLIP. In the first chapter, for instance, I tried to recall the days and weeks following my mother’s death — a traumatic life event that led me to develop a childhood eating disorder.

I knew that to write effectively about this period, I had to try to re-inhabit my younger self and recall the sensations I felt (or wanted to feel) at the time. At one point, I revisited my childhood home and searched in the attic for my old journals. Holding one in my hands, I remembered thinking of that journal as a form of escape and release during a time when my mother’s death had left me feeling emotionally numb. I wrote about this experience in Chapter 1:

The first journal I opened had a picture of Claude Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Giverny on the cover. One of my sixth-grade teachers had given me the journal a few days after my mother died and suggested I use it to record memories of her. I remember staring at the journal’s cover and wishing I could slip into that garden; I wanted to smell the powdery scent of irises, to feel the sun’s dappled light on my skin, to be somewhere far away.

As an adult looking back, it was important for me to relay the senses that my 11-year-old self longed for in the aftermath of my mom’s passing.

3.) Listen for good quotes and for dialogue.

One way to capture the sense of hearing is to listen for moments when your interviewee’s voice sounds loud and clear. This sound often takes shape in the form of quotes that express one or more of these key elements: opinion, emotion, or reaction. The best human quotes:

Explain something about the interviewee

Let audiences hear the interviewees’ voice

Express something better than you can as the writer

Introduce and sustain a human voice in the story you’re writing

Advance and enhance the story

As journalists, we’re trained to listen for good quotes (what people tell us), but we’re not as well trained in the art of capturing dialogue (what people tell others). My mentor Roy Peter Clark once told me to think about it this way: Quotes are heard. Dialogue is overheard.

When interviewing someone, don’t just hear what they’re telling you; listen for the moments when they’re interacting with the people around them. I did this several times when interviewing people whose narratives I featured in my book. At one point, I was interviewing a mother whose son unexpectedly ran into the room. Listening to her interact with him enabled me to see a different side of her. I was recording the interview, so their dialogue was part of the recording. With the mother’s permission, I used a short snippet of their interaction in one of my book’s original chapters.

You can also keep dialogue in mind when interviewing two people at the same time. Consider: How do they riff off each other? Do they complete each other’s sentences? When do they complement each other and/or contradict each other? Another way to think about all of this is that quotes are about the action, dialogue is in the action. Whenever possible, try to capture both — and remember that the human voice can be a powerful form of detail.

4.) Vacuum in the scene.

This is a tip I learned many years ago from longtime journalist Tom French, and it has stuck with me ever since. The idea is to always pay attention to a person’s surroundings.

This of course works best if you’re interviewing someone in their natural environment — their home, their office, the park where they walk their dog, etc. But even if you’re conducting interviews via Zoom, you can “vacuum” up any details that you see in the background.

If you’re interviewing someone in their office, make note of the books on their shelves. What titles do you see? Which books are prominently displayed? (Or is their office devoid of books altogether?) If you’re interviewing someone at their home: Are there photos on the person’s living room mantle? If so, who’s in the photos? Does the person have a dog that’s barking in the background? If so, what’s the dog’s name?

These can be nice icebreaker questions, or softball questions in between tougher ones. The details you capture from these observations and questions won't all end up in the story, but even including one or two can help make a story stand out.

5.) Ask interviewees to share visuals.

Sometimes when I’m interviewing people about difficult topics, and I sense that they’re getting emotional or need a reprieve, I’ll ask to see some photos. I did this when interviewing a young woman who, like me, developed an eating disorder after losing her mother. She was still in the thick of the grieving process when we spoke, and I could tell that it was understandably difficult for her to talk about her mom’s death.

So I pressed pause and asked, “Do you have any photos of you and your mother that you’d want to share with me?” She seemed surprised, but delighted, that I asked. We were talking via Zoom, so she couldn’t show me anything in person. But she walked away for a minute and then came back with photos that she held up to the camera on her computer screen.

As I looked at the pictures, I asked her to tell me about them. This seemed to put her at ease, and it opened up a rich line of storytelling that shifted the narrative from her mother’s death to the life they shared together. I was able to learn so much more about her — and her mother — during the process.

6.) Draw your own visuals.

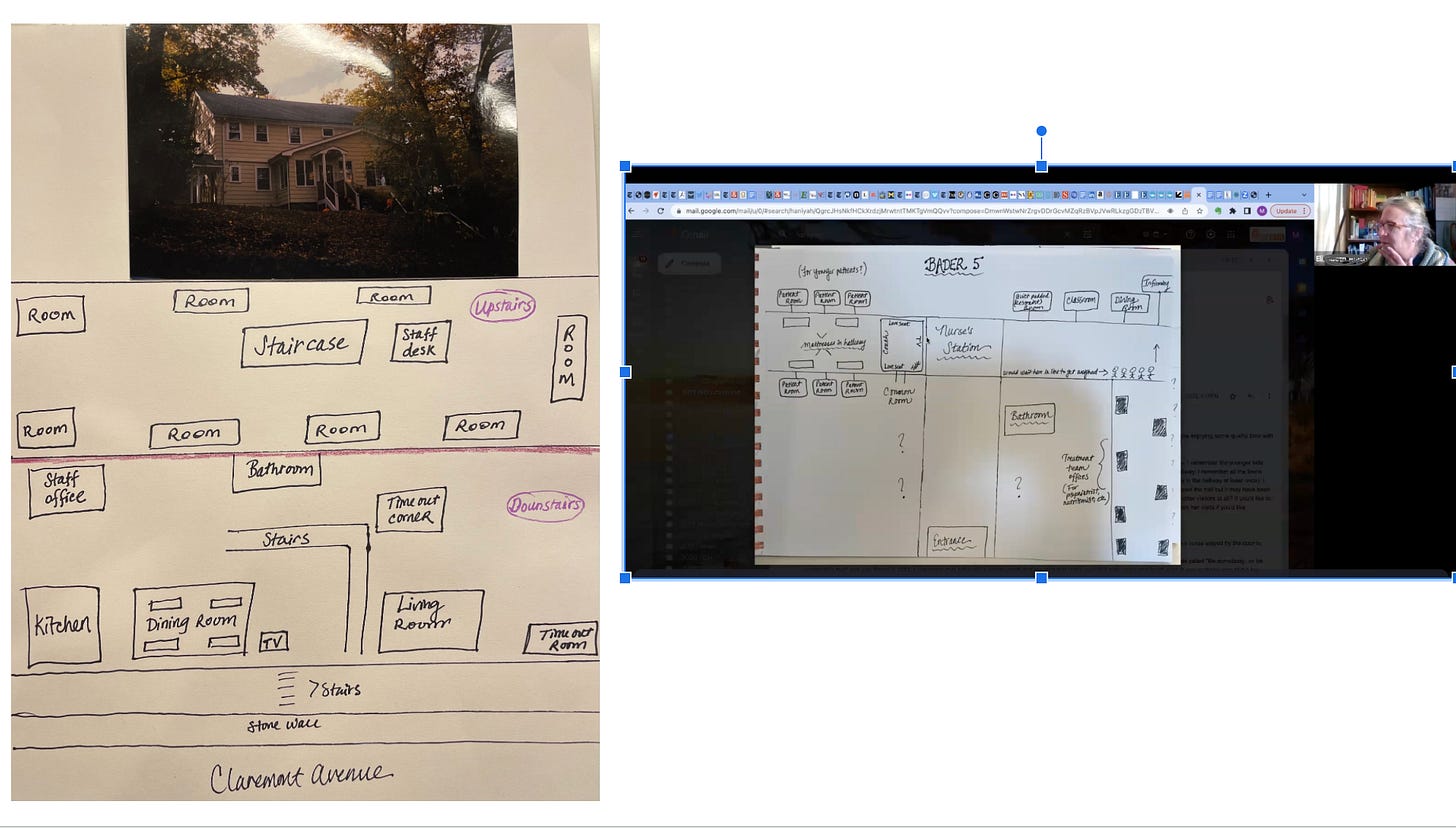

While doing reporting for my book, there were many times when I needed to corroborate my memory of places from my past. This was the case when writing about the residential treatment center where I lived for seventeen months while getting treated for my childhood eating disorder.

The center shuttered years ago, but I traveled to Massachusetts to walk the grounds and to jog my memory of the neighborhood where it was situated. I vacuumed in the scene, taking note of the evergreen trees and Victorian-style homes that lined the streets, and the view of Boston’s skyline in the background. The building I lived in had been razed a decade prior, so there was no way I could access it. Instead, I turned to photos, memory, and interviews with former staffers and patients to recreate a sense of place on the page.

Prior to interviewing a former staffer, I drew a picture of the building’s layout and showed it to her during our Zoom call. We talked about each part of it, and at a certain point it felt like we’d gone back in time and were together in that building again. The drawing sparked a meaningful conversation that helped fine-tune my memory and hers. Together, we were able to help each other fill in the blanks and uncover long-lost details.

In many ways, interviews offer up a chance to excavate the past — and better understand the present. If you view them as a process of discovery, you’ll no doubt find compelling details along the way.

A related exercise: Do close readings of other well-written feature stories or narrative nonfiction books and consider: What questions might the writer have asked to get to that level of detail? This reverse-engineering can be a fun and creative way to hone your interviewing skills on your own time. You can also check out last week’s tips on interviewing for detail.

I’d love to hear from you! Which tip resonated with you the most? Do you have others to share?

Dear Mallory,

Your advise is so valuable. I really like all your tips about feeling in the body when interviewing or researching. Very often when we write especially for an assignment we are concentrating on our brain…

I also thought about giving some details about the person we are interviewing. I realised that when reading portraits of people, the journalist feels allowed to describe how a woman is dressed but doesn’t do the same if it is a man 🤔. I do agree with you that describing the environment where is the person you are interviewing gives lots of information also. That’s why it was so frustrating during COVID not being able to actually meet people and itw by phone…

All the best to you and looking forward to read you !

Elena

I love the vacuum metaphor! You're so right - all my favorite profiles of interesting people suck up sensory details in the subject's environment.