Writing prompt: Identify a meaningful object & tell its story

For my Longform Feature Writing course last week, I asked my students to bring an object to class. We had just finished reading a few pieces that featured objects — including this Pulitzer-winning Atlantic piece by Jennifer Senior— and it seemed like a fun way for students to apply our class readings to their own writing.

While leading the exercise, it struck me that this could be a helpful prompt for the Write at the Edge community too. The steps are simple: find an object that is meaningful to you, tell someone else about it (a partner, a classmate, a colleague, heck even your pet), then write about it.

This exercise works especially well if the object relates to a piece you’re currently writing or one that you aspire to write. It can work for personal essays and memoirs but also when writing about other people — sources in journalistic stories, for instance, or characters in novels.

I relayed all of this to my students, who each brought their object to class and shared the story behind it during a roundtable discussion. I asked the students to consider:

What memories (if any) does this object conjure?

How can you illustrate the place, time period, and people associated with this object?

What story does it tell?

What universal theme (resilience, love, loss, ambition, identity) does it represent?

Why does it matter so much to you?

How does it help you as a writer? (Could it, for instance, help you to write a scene in greater detail? Could it help you weave some levity into an otherwise heavy piece? Could it help you to better illustrate a part of your past? Could it be an entry point for writing about a topic you’ve been avoiding?)

Together, as a class, we learned about an array of objects: books, a baseball, a wedding ring, a family photo, a camera, a painted rock, a dog-bitten cross. In talking about these objects, we also learned a lot about one another and the personal stories we hold dear.

The students then had a half-hour to write ~300 words about their object and what it reveals. I didn’t make them share their writing, partly due to time constraints, but I did provide a discussion forum for those who wanted to do so. Afterward, many students told me that the exercise unleashed newfound ideas and inspiration.

I’ve completed this same exercise many times and have had similar reactions. Now that I’ve finished writing my book, SLIP: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery, I considered the many objects that were helpful to me along the way. Since the earlier, personal parts of the book look at how I developed an eating disorder after my mother passed away, many of the objects are related to motherhood and childhood illness. I couldn’t possibly include them all in one post, but here are a few:

I’m lucky to have hundreds of photos from my childhood, thanks in large part to my father. He enjoyed taking family photos, and he saved them all. I found the pictures especially helpful when writing about the toll that breast cancer took on my mom’s body. It was difficult having to recall painful memories from her three-year struggle with cancer, but looking at pictures helped. They jogged my memory and made it easier to write about the ways my mother’s appearance changed the sicker she got. The picture on the left shows me and Mom just before her diagnosis. The picture on the right shows her on Christmas Day 1996 (at age forty), about six weeks before she passed away.

My mom cross-stitched this beautiful fall scene, which hangs in my home office. I often looked up at it when writing my book, and I ended up including it in one of the chapters. Seeing it helped me think about how my mother found comfort in cross-stitching — a lifelong hobby she didn’t want to let go of when she got sick. Cross-stitching seemed to be a way for her to preserve her sense of self in the face of a disease that threatened to take it away.

As a kid, and especially after my mother died, I escaped into books. One of my favorites was Harriet the Spy. I wanted to be like Harriet, so I got my own “spy notebook” and pretended to snoop on my neighbors. The Lisa Frank notebook holds all of my “top-secret” spy notes, and it makes an appearance in my book. This object offers up a point of relatability for readers who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s like me, and it also helped me weave some levity into an otherwise heavy chapter.

After my mom passed away, I developed an eating disorder at age twelve. At the time, every meal, every bite, was a struggle. I didn’t like talking while eating, and the silence at mealtimes was deafening. Hoping to help, my father bought this book, which features mini narratives about fathers and daughters. He read it to me during every meal — to break the silence but also to show his love for me. I recently found our original copy in my childhood home and re-read it when writing SLIP. Though only mentioned briefly in my book, this object helped me show my father’s support during an especially fraught time. That’s one of the beauties of objects; they can empower writers to show and not just tell.

This pot reminds me of the one my mother and I used when boiling lobsters during summers in Massachusetts. We loved eating lobster together, and part of the fun of it was going to the store to pick out the biggest ones. We’d bring the lobsters home, then put them on the kitchen floor for a “lobster race.” The first one to cross the finish line won, meaning it went into the pot last. Understandably, some might consider this to be inhumane. But for me, it has always been a comforting reminder of how my mother tried having fun with food. I write about this pot in the book, during a part where I talk about my recovery from anorexia. One of the ways I worked toward recovery was by trying to reconnect with foods I used to eat with my mother, including lobster. (Somewhat ironically, I’m now a vegetarian, so I have not re-enacted this pastime with my own children!)

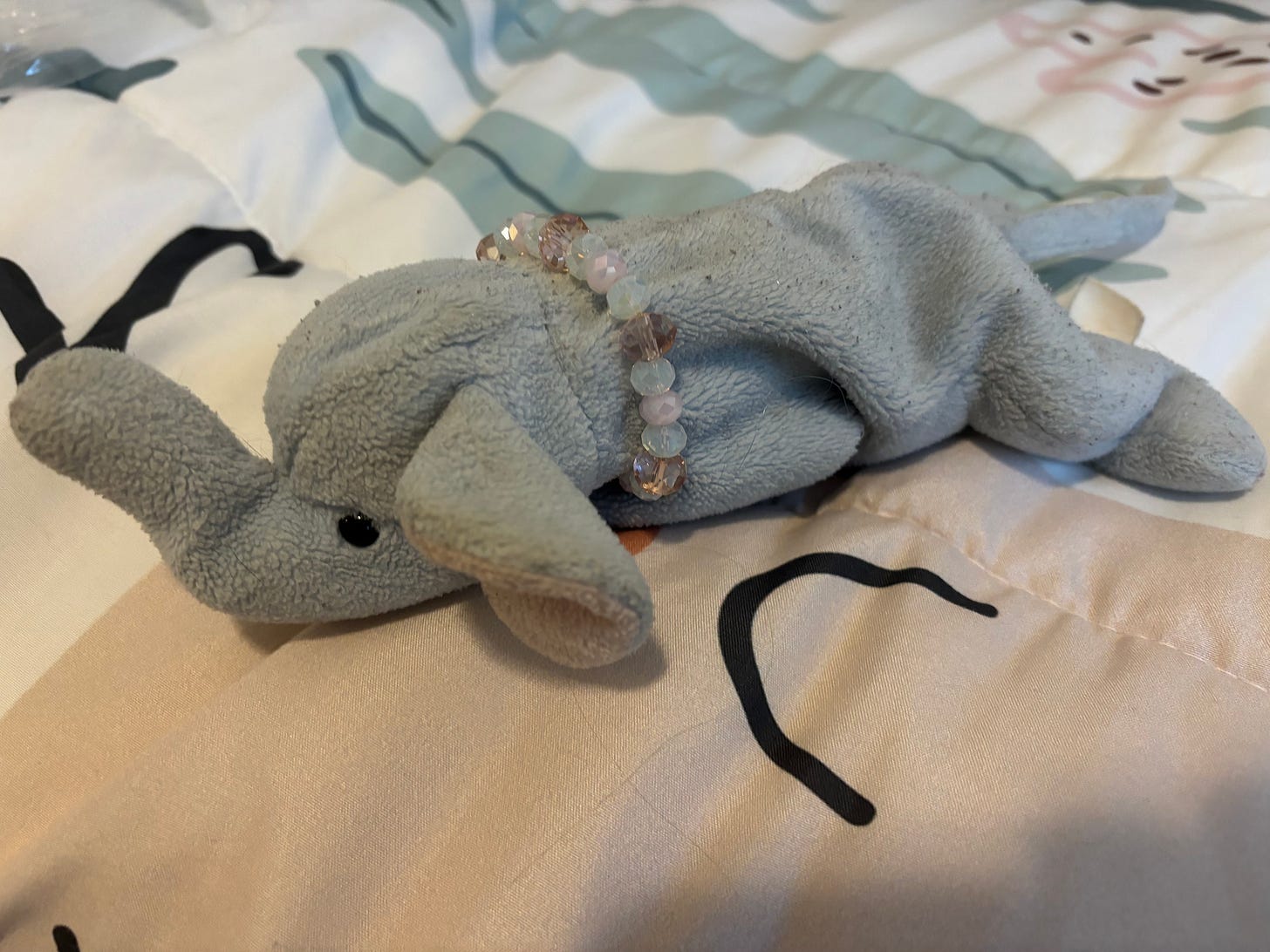

This is Peanuts the Beanie Baby. She doesn’t make an appearance in the book, but I can see myself writing an essay about her at some point. The essay wouldn’t be so much about her but about all that she represents. She was one of my favorite stuffed animals as a kid, and she was so well-loved that a hole formed under her right arm. My mother, the cross-stitcher, sewed her for me. I’ve always loved seeing her stitches — little reminders of how my mother mended wounds. Peanuts now belongs to my eight-year-old daughter Madelyn, who sleeps with her every night. Madelyn has loved Peanuts so much and for so long that the stitches my mother made started to fall out a couple years ago. My mother-in-law added some new stitches, careful not to remove my mother’s. I love all the ways in which this one tiny objects symbolizes so much about motherhood and maternal lineage.

How about you? If you were to do this exercise, what object would you choose? I’d love to hear about your object and the story behind it!