How writers can find meaning in the lost art of letter-writing

Plus, galley copies of my book have arrived!

Hi friends,

I hope you’re having a good holiday season and that you’re getting a bit of a break.

I was going to give myself a break by skipping this week’s newsletter, but then I thought about how writing is my respite. In the quiet early mornings, when the house is still and the family is asleep, I relish my uninterrupted time to do what I love: write.

There was something, though, that I did take a break from this month: preparing and mailing dozens of holiday cards. Bogged down by work, book-related deadlines, and kid activities, I had to let the cards go. Doing so felt like a reasonable way to preserve my sanity and conserve some energy.

Although I let my holiday card tradition lapse, I actually mailed more handwritten letters in 2024 than I have in years. Most of them were related to reporting I did for my forthcoming narrative nonfiction book, Slip: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery. In mailing letters to hard-to-reach sources, I thought about the power of letter-writing — to make a lasting mark, to flex different writing muscles, to connect with people who may be hard to reach, and to resurface childhood memories.

I wrote about all of this for a recent story that was published on Harvard University’s Nieman Storyboard site. Drawing upon tips from my own work and from other journalists, the piece looks at how journalists (or any writer, really) can find meaning in the lost art of letter writing. I encourage you to check it out.

My own affinity for handwritten letters dates back to childhood, when letter-writing was my go-to form of written communication. My mother would take me to the Hallmark store and buy me stationery, which I would use to write thank-you letters and occasional notes for my parents. Even then, I liked writing not just for myself, but for others.

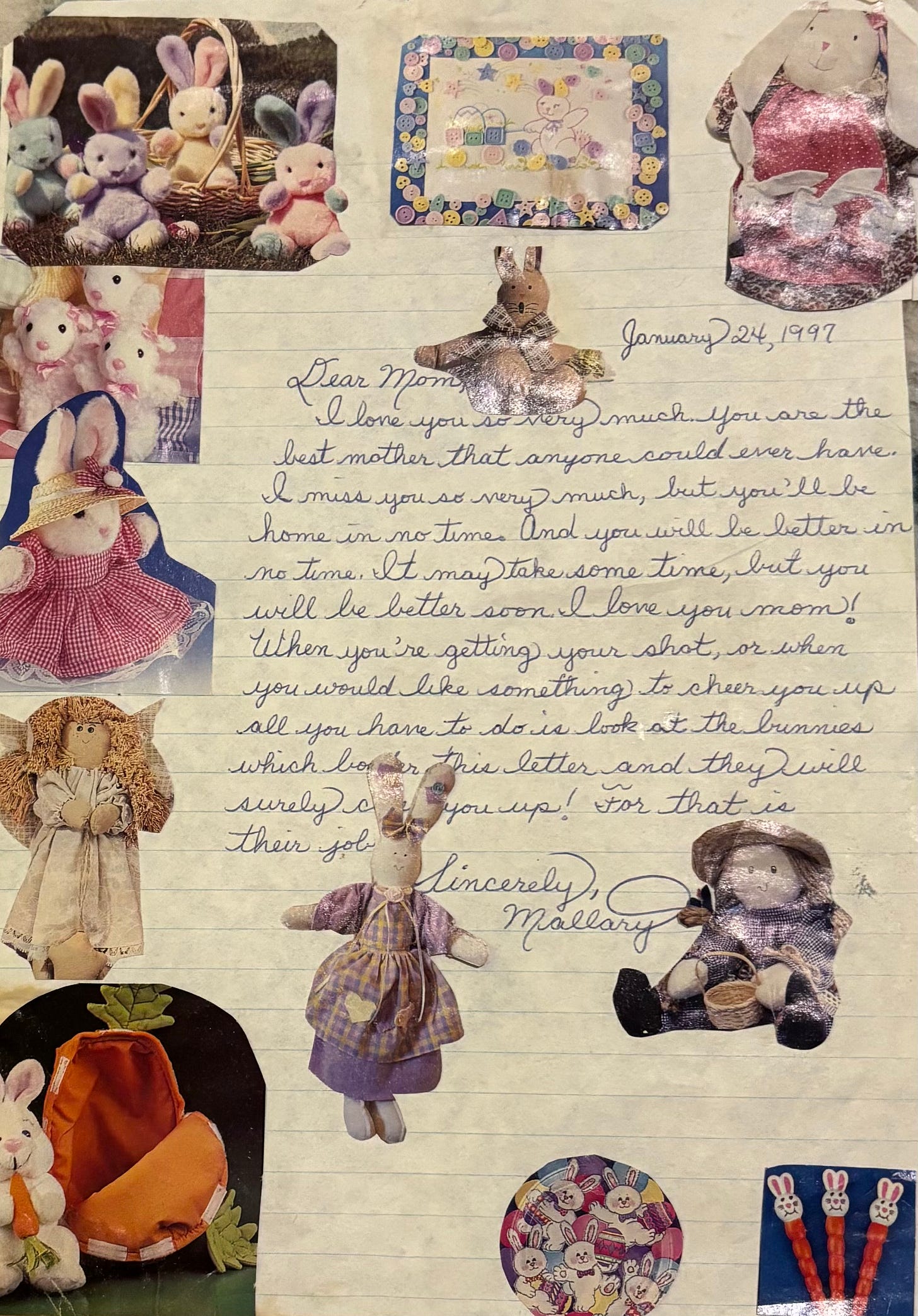

After my mom got sick with breast cancer when I was 8, I wrote her letters of encouragement, hoping they might take away her pain and help make her better. But three years later, she passed away.

I was only 11 years old at the time and desperately wanted to stay in touch with my mother. I wrote to her often and found comfort in pretending she was on a trip somewhere far away and would one day come home. For better or worse, letter writing became a way of escaping the obstinate reality of what I knew deep down to be true: she was never coming back.

I continued writing letters in the year following my mother’s death, especially after I got sick and was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. As I write about in Slip, I was hospitalized for weeks at a time and would often mail letters to my father while I was away. He would write me back, becoming a paternal pen-pal. I kept on writing letters to him for the 17 months when I was in residential treatment. In the midst of so much distress, we both found it easier to write about hard truths than to speak of them.

I still have so many of the letters I wrote to my mother and father, and I revisited them when writing Slip, which blends personal narrative and reportage to tell my own story and those of many others with eating disorders. The letters were powerful source materials, and I ended up quoting from several of them.

As I pored over the old notes, it occurred to me that letter-writing could be a good way of reaching hard-to-access sources who I wanted to interview for my book. I ended up mailing hand-written letters to a few of these sources, and each one led to an interview that I may not have otherwise gotten. Over the past couple of months, I’ve also written letters to the early readers of my book, as well as the authors who blurbed it. I made origami heart bookmarks to accompany them and tucked one inside each envelope.

And although I didn’t mail any holiday cards this year, I did write to one person on Christmas Day: my mother. In a handwritten letter, I told Mom I missed her — especially at this time of year, when the residual pain of loss flares up for so many of us.

I also shared some exciting news with her: the galley copies of my book Slip just arrived, meaning I can finally hold the book in my hands. When telling my mom about the book, words flowed out of me so quickly that my hands had trouble keeping up. Toward the end, I shared an Anna Quindlen quote that I’ve always loved: “Writing is the gift of your presence forever.”

I’ve thought about how I hope my book will be a gift to my two children, who will one day read it and have a lasting account of their mother’s story. I hope it’s also a gift to anyone navigating a middle place — between loss and closure, between acute sickness and full recovery. And, as I mentioned in the letter, I consider the book to be a gift for my mother. Filled with many mentions of her, the book will help keep her memory alive and ensure she’s never forgotten.

The galley reveal of Slip!

I like to think that, had my mom gotten to see me hold my galleys for the first time, she would be jumping up and down with excitement. She probably would have already pre-ordered 10 copies, frugal though she was. Maybe she would have even written me a congratulatory note.

This holiday season, I’m grateful to everyone who has pre-ordered so far. I love knowing that the book will soon be in your hands, too, when it comes out in August. And if you haven’t yet pre-ordered, I hope you’ll do so as a gift to yourself and/or anyone in your life who would benefit from a book that explores eating disorder recovery alongside grief/loss, motherhood, and the in-between spaces we find ourselves in when we’re no longer sick but not fully better.

During this week in between Christmas and New Year’s, I’ll be working on my next assignment: handwriting letters to the 20 early readers/reviewers who I’ll be giving galleys to in the new year.

Here’s to lots more writing in 2025!

I’d love to hear from you. Do you still write letters from time to time? If so, does the format lead to a different type of writing or voice? Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section.